Semiconductor in numbers: Water utility investments behind US mega-fab projects

Share this insight

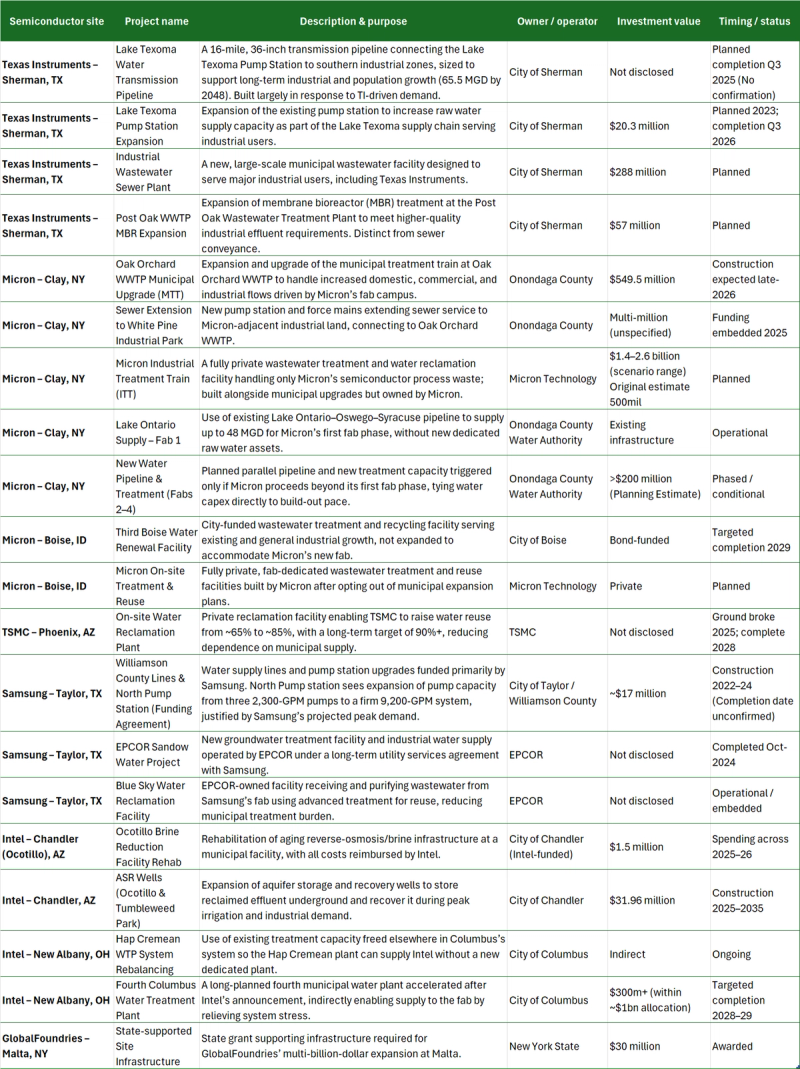

This table shows the scale and structure of water utility investments backing some of the largest semiconductor projects in the US. It highlights where public utilities are expanding municipal systems to unlock capacity and where chipmakers are opting to fund dedicated, fab-specific infrastructure. Across the country, investment is splitting into two distinct tracks: public upgrades designed to meet capacity driven by industrial use, and private treatment and reuse systems for capabilities that go beyond municipal limitations.

Public systems stretched by mega-sites

Micron’s $100 billion Clay, New York mega-site illustrates how municipal water infrastructure is being reshaped by semiconductor demand. Onondaga County is advancing a $549.5 million upgrade of the Oak Orchard wastewater treatment plant, alongside sewer extensions and new pump stations, to unlock capacity for industrial and residential growth linked to Micron. The upgraded system is designed to treat up to 20 million gallons per day and is framed as a regional economic development asset to future-proof for further industrial growth, rather than a Micron-exclusive facility framed as a regional economic development asset to future-proof for further industrial growth, rather than a Micron-exclusive facility.

At the same time, Micron is funding and operating a separate, dedicated industrial wastewater treatment train for process effluent that cannot be handled by conventional municipal systems. Costs for this private facility have escalated from early estimates of $500 million to between $1.4 billion and $2.6 billion as a worst-case scenario.

A similar capacity-relief logic underpins Intel’s New Albany, Ohio project. Columbus committed to supplying 1.5 million gallons per day for Intel’s first phase and accelerated its long-planned fourth water treatment plant, now a roughly $1 billion programme within the city’s capital budget. Although the new plant will not directly serve Intel, it frees up capacity elsewhere in the network, allowing existing assets to support the fab and other fast-growing users. The city has also acknowledged ongoing uncertainty around future expansion, noting that additional water sources will be required as demand grows.

Private treatment and reuse as the default

At TSMC’s north Phoenix campus, the company’s water strategy has significantly reduced pressure on municipal supplies, but only after substantial public investment helped secure the project. Under its development agreement with the City of Phoenix, TSMC was granted access to up to 11.4 million gallons per day (MGD). By treating and reusing most of its process water on site, however, the city ultimately only needs to deliver around 4.2 MGD, roughly one-quarter of total demand.

Despite this reduced long-term draw, Phoenix committed major infrastructure upgrades to attract TSMC. In 2020, the city approved a development agreement, including roughly $137 million for wastewater infrastructure and public water assets.

Micron has reached a similar conclusion in Boise. After initially exploring an expanded municipal water renewal facility, Micron opted to build and operate its own treatment and reuse infrastructure. The City of Boise is now proceeding with a smaller, publicly funded facility sized for existing users, while Micron’s fab remains separate from the municipal water recycling system.

Intel’s Ocotillo campus in Arizona has ongoing investment in brine reduction, aquifer storage and recovery wells, and rehabilitation of ageing treatment assets. These projects are fully reimbursed by Intel, reinforcing the trend toward customer funded lifecycle management where industrial water use dominates.

Cost sharing models in Texas

In Sherman, municipal investment in long-distance pipelines, pump station upgrades and wastewater treatment is framed as long-term industrial growth infrastructure, with Texas Instruments expected to subsidise part of the cost. The city has constructed a 16mile water transmission pipeline from Lake Texoma and is expanding industrial wastewater treatment capacity to meet projected demand through 2048.

In Taylor, Samsung’s project follows a clearer cost sharing and private utility model. Municipal systems are expanded to provide core supply, with Samsung committing at least $17 million to water infrastructure upgrades and covering a share of any excess costs. Dedicated industrial supply and reclamation facilities are owned and operated by EPCOR under long-term agreements directly linked to Samsung’s demand, including the Blue Sky Water Reclamation Facility.

Share this insight

Organizations

Samsung Austin Semiconductor

Intel

Micron